top

Project Overview

Learning, Design, and Technology (LDT) faculty at the University of Georgia (UGA) are known for being “front runners,” adopting “cutting-edge” and innovative approaches to teaching and learning. For example, LDT at UGA is well known among LDT programs for “The Studio” approach developed 15 years ago. In hopes to continue the legacy of innovative learning approaches, there have been discussions amongst the faculty in terms of what the next innovation should be with the IDD program. The inspiration for this instructional project is originated from this innovative tradition in this program and the extensive research of Dr. Janette R. Hill on online teaching and learning and negotiated learning environments.

The Global IDD project endeavours to create a practically negotiated learning environment to satisfy students’ diverse logistical needs, affective needs and cognitive need. In a commitment to meet the needs of all of our graduate students, we piloted a flexibly accessible delivery strategy in the spring of 2018 in two graduate courses of LDT, with innovative use of various technological tools to combine 3 modes of learning together, i.e. face to face on site, synchronously online, and asynchronously online. The practically negotiated learning environment (PNLE) is grounded in a pragmatic constructivist learning-centered design of a community of inquiry. It strives to accommodate various pedagogical strategies and learning activities, offering high level of flexibility to all participants of the learning community, including the students and the instructors or facilitators.

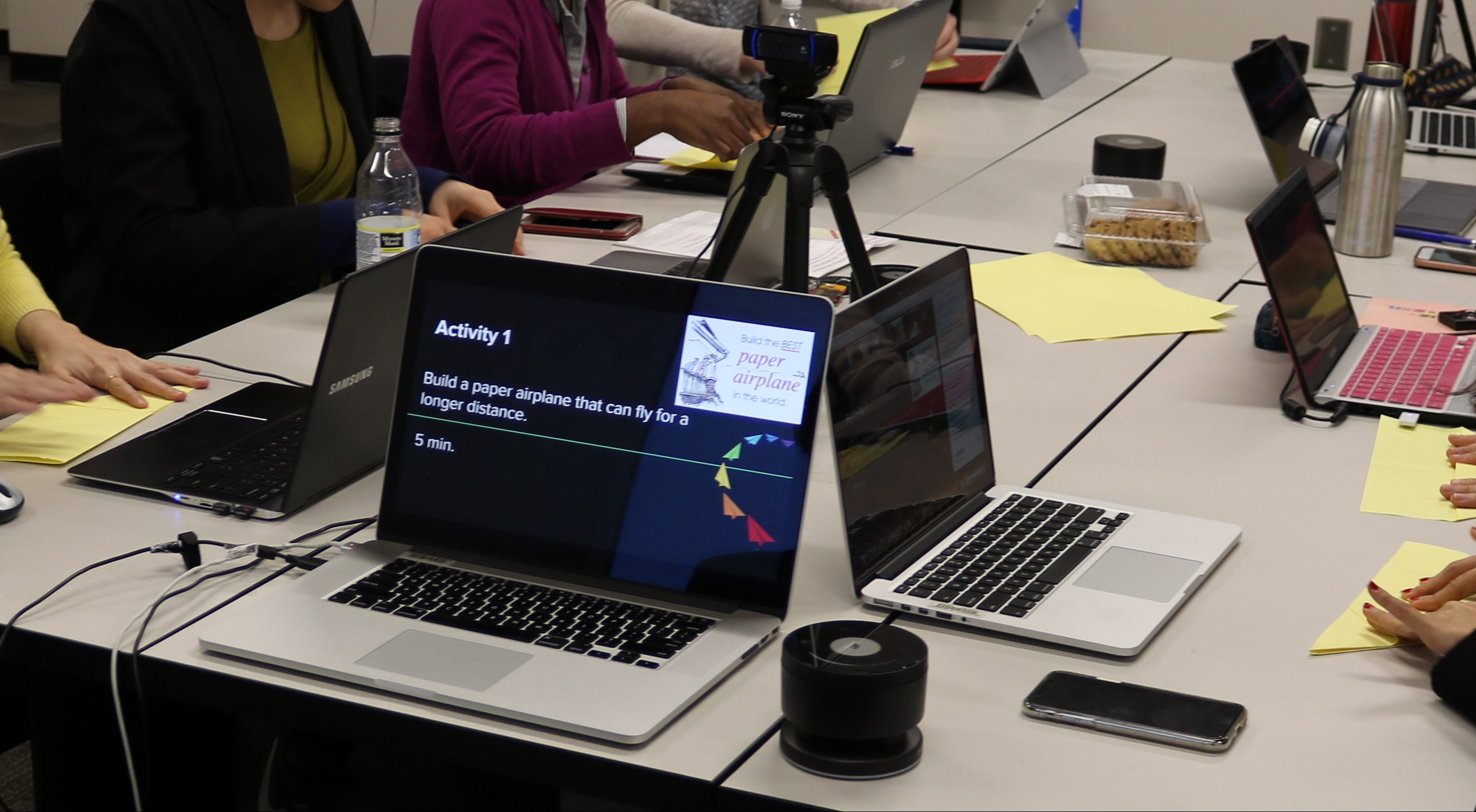

In the pilot implementation, this innovative instructional design practice was adopted in two graduate courses, EDIT 6170 and EDIT 6210, using web conferencing tools, desktop recording tools, multi cameras, multi screen displays, and mic-speaker system. Instructors and students joined together once a week for face-to-face and synchronous interactions, which were recorded and immediately uploaded for the asynchronous students. Various technologies were used to enable the interactions in real and delayed time.

Formative evaluation shows that students generally have a positive learning experience in both classes. They are satisfied with the use of Zoom as the major tool and the overall use of technology. The flexibility of attendance mode is highly appreciated. In general, face-to-face onsite students feel more satisfied than remote students. Interviews with instructors reveal that students’ performances are comparable with previous classes where only one mode of learning was involved. Dr. Choi even said this was the best class he had ever had and he was especially impressed by online students’ high level of commitment and expertise. Challenges, however, still lies in how to organize small group breakout sessions in class more efficiently and effectively, how to include asynchronous online students in the dynamic interaction, and how to manage the cognitive overload experienced by instructors.

This handbook is for the faculty members in LDT who are interested in teaching in this practically negotiated learning environment (PNLE) to bring students’ learning experiences to a new level. We will first introduce the theoretical bases and a conceptual map of PNLE. We then introduce the 4 key design principles based on the conceptual map. In “Technological Practicality”, we will examine the basic technological considerations we had when we tested and chose suitable tools. “Recommendations for Implementation” will give the instructor a clear view about the technology setup in the physical classroom and some troubleshooting strategies. At last, we consider the pedagogical practicality in PNLE and suggest technological tools for major classroom activities with specific guidelines. More resources can be found in our website http://ldtglobal.commonsmith.com/

Conceptual Framework

Introduction

In a digital era, there is a need for flexible methods of delivery to meet the needs of a more diverse learner population (Bates, 2015). Students increasingly need ways to attend class in ways that are convenient and meet the demands of 21st century life (logistic needs), and ways to make connections and engagement that fosters learning within a given course and to create global professional networks to sustain their careers (affective and cognitive needs). On the surface level, online learning, whether synchronous or asynchronous, has made the first step to meet the students’ logistic needs for flexibility; however, the choice and determination of delivery mode is still at the hands of the institution and instructors (Irvine, Code & Richards, 2013).

In recent years, there are some programs or courses attempting innovative means to delivery face-to-face and synchronous instruction in real time simultaneously (Bower et al., 2015), bringing two groups of learners divided by geographies, time zones and contexts into the same connected learning space (Henriksen, Mishra, Greenhow, Gein & Roseth, 2014). Nevertheless, none of them aspire to accommodate three modes of learning, i.e. face to face on site, synchronous online and asynchronous online, at the same time.

Meeting Students’ needs

Logistic needs

Nontraditional students need more flexible ways to attend class to meet the demands of their busy daily schedule, yet they still desire a comparable learning experience no matter what learning mode they choose. Web conferencing tools and advanced recording tools allow students freedom to decide when, where and how they take courses on a weekly basis, especially for synchronous and asynchronous online students. The flexibility is beneficial to face-to-face students as well when they are unable to attend a class onsite.

Affective needs

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Deci & Ryan, 2000) posits three basic human psychological needs, namely autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy means a sense of agency and self-determination, which are highly related to intrinsic motivation. Competence refers to the self-efficacy to have the relevant skills to succeed, and it enhances the intrinsic motivation accompanied by a sense of autonomy. Relatedness refers to a sense of belongingness and connectedness, which majorly deals with extrinsic motivation. SDT maintains that social, cultural, and contextual conditions that facilitate people’s perception of autonomy, competence, and relatedness can foster the most volitional and high quality forms of motivation and engagement for activities, including enhanced performance, persistence, and creativity (Deci & Ryan, 2000). In educational contexts, satisfaction of students’ diverse affective needs are essential to students’ performance and overall well-being. Butz, Stupnisky, Peterson and Majerus (2014) reported significant correlation between affective needs satisfaction and motivation for both online and on-campus students in a synchronous hybrid graduate program, and there were few significant differences between the two unique groups in terms of need satisfaction, motivation, and perceived success. It implies that synchronous hybrid learning environments may be able to provide a more equitable approach to online education (Butz et al., 2014).

Cognitive needs

Students have a wide variety of learning styles. Students’ various learning styles are influenced by their cognitive and affective traits. To satisfy the varying cognitive needs of the students, we propose learning-centered approach as opposed to learner- or student-centered. Learning-centered leaves room for the negotiated learning environment. Students are encouraged with greater and greater autonomy, but in a position of autonomy students have the freedom to request more direction and scaffold. Learner- or Teacher-centered distinctions maintain a fixed view of designing learning environments that may be impractical and inflexible for the varied needs of a learning community.

In order to satisfy students’ diverse needs, our project takes a further step to to combine the three delivery modes in one course. It will afford a higher level of flexibility, which means students have the freedom to choose any of the three attendance modes from week to week. It strives to ensure all students have comparable learning experiences regardless of location or attendance mode (Cain, Bell & Cheng, 2016) through interaction and connection with participants in the learning community. As we have observed, however, challenges of creating a flexibly accessible learning environment lie in the design and implementation of both pedagogical strategies and technological systems that enact those comparable learning experiences (Cain, Bell & Cheng, 2016).

Therefore, the Global IDD project aims at designing a flexibly accessible learning environment to address learners’ logistic, cognitive and affective needs, taking into consideration pedagogical and technological practicality as a way of filtering and delivering student needs so as not to try and meet all needs, but a negotiated balance where needs are met flexibly throughout the course of learning. This negotiated balance requires a learning environment and community that is conducive to meeting the various student needs in practical ways.

Practically Negotiated Learning Environment

We propose a framework that draws from Janette Hill’s (2013, 2017) negotiated learning environment and the Community of Inquiry conceptualization of social, teaching, and cognitive presence (citation) as the basis of a practically negotiated learning environment (PNLE); furthermore, although constructivism is an underlying theoretical/philosophical frame of a PNLE, we believe that “constructivism” is too vague a term, and instead will argue that pragmatic constructivism is the more relevant frames a practically negotiated learning environment.

Negotiated learning environments (NLE) allow the balance of individual and external priorities that affect learning (Hill et al., 2013). A hybrid of informal and directed learning environments, NLEs typically have an underlying constructivist philosophy and epistemology, owing to the promotion of learner autonomy but in a more formal context (Hill et al., 2013).

Incorporating different philosophical bases of directed and informal LEs is a fundamentally incompatible task if we pursue ideological purity. Furthermore, practical concerns of Jonassen’s CLE and Hill’s NLE above, such resources, tools, scaffolds, and assessments, may hinder or reverse the pure versions of a directed or informal approach in the context of a learning space (Dr. Branch’s diagram of Learning Space?). We suggest that a practically negotiated learning environment has a robust affinity with a hybrid, synchromodal form of course delivery.

Social, teaching, and cognitive presence

A PNLE promises a higher degree of interaction among student, teacher, and content due to the nature of negotiating the components of learning. The Community of Inquiry framework (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000) posits assumes learning occurs within the the learning community through the interaction of three core elements: cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence (See Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Community of Inquiry model (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000, P. 88)

Cognitive presence means the extent to which the participants in a community of inquiry are able to construct meaning through sustained interaction and communication. It is a fundamental goal and critical component of the learning process.

Social presence refers to participants’ ability to project and present themselves to the other participants in the community of inquiry as “real people” with distinct social and emotional characteristics. It functions as facilitative factor for cognitive presence, supporting the process of critical thinking carried on by participants.

Teaching presence is the responsibility to design and facilitate the educational experience, including presenting learning content, designing learning activities, and development assessment tools. It supports and enhances social presence and cognitive presence in order to realize certain educational objectives. Although this responsibility is usually taken by the teacher, it may be performed by any one participant in a Community of Inquiry.

Social presence in education has many benefits (Richardson, Maeda, Lv, & Caskurlu, 2017), yet all presences seem to overlap. Teaching presence may exert a stronger influence on all the other types of presence, including social presence. A hybrid, synchromodal learning environment promises more complex and higher degrees of cognitive load (Bower et al., 2014) and technological-mediation among the three types of presences. As a result, practical considerations circumscribe the learning environment. Issues such as the class access and delivery modes, affordances of the technology, and technology-in-action, combine with issues of student needs to result in a practically negotiated learning environment.

Practical learning environments

Practical learning environments refer to learning spaces which implement and meet a negotiated learning environment and students’ learning needs with technological and pedagogical practicality. It is important to identify the intersection of technological practicality and pedagogical practicality because technological affordances need to support pedagogies to realize negotiated learning environment which accommodate diverse learning needs. In conclusion, “the importance of alignment among psychological, pedagogical, technological, pragmatic and cultural foundations of a learning environment” (Land, Hannifan & Oliver, 2012, p. 6) cannot be stressed enough.

Concept map of PNLE

As shown in the Figure 2, practically negotiated learning environments adopt values from diverse learning environments such as instructor-centered learning, online learning, and constructivist learning environment. Students learning needs which result from their cognitive, affective, and logistical needs are primary concern of PNLEs. Each learning activity is designed at the intersection of technological and pedagogical practicality.

Figure 2. Conceptual map of practically negotiated learning environments.

Key Design Principles

With pragmatic constructivism, self-determination theory, learning-centered approach, and negotiated learning environments as underlying theoretical bases, the practically negotiated learning environment we propose is designed with the guideline of four key principles, namely flexibly accessible, flattening hierarchy, participation and presence, and on-going and dynamic interactions.

Flexibly accessible is a core principle, which means students have the autonomy to choose from the three modalities of learning, that is, face to face onsite, synchronously online or asynchronously online to fit their logistical needs.

Participation and presence. Provide ways for students to engage in learning that meet their regular as well as just-in-time needs. We were committed to blending three modes of interaction (face-to-face, synchronous, and asynchronous) simultaneously. As students meet face-to-face and synchronously, the course is recorded in real-time and then uploaded within 24 hours. We believe that this blend enables increased participation and presence (Richardson et al,, 2017) for all students.

Flattening of hierarchies. We also sought ways to breakdown the traditional power structure in a classroom, developing a context in which all participants – instructors and students alike – have the opportunity to be teacher and learner. In doing so, we worked to enable a more negotiated open-ended learning environment to best meet learning needs (Hannafin, Hall, Land, & Hill, 1994; Hill, Domizi, Kim, & Kim, 2013)

On-going and dynamic interactions across participants and content. We wanted instructors and students to have the ability to have on-going and dynamic interactions with each other as well as with content (Moore, 1989). We sought to create a context in which the free flow of information and ideas can more readily occur by providing multiple modes of access to meet learners’ needs and flattening the hierarchies in the learning environment.

Technological Practicality

Minimal equipment

First of all, we identify minimal equipment to implement the practically negotiated learning environment and potential challenges as shown in Table 1. It can work well with small size of onsite group without a TA.

Table 1. Minimal equipment for a practically negotiated learning environment

|

Minimal equipment |

Advantages |

Potential challenges |

Possible solutions |

|

|

|

|

Next minimal equipment

However, the effectiveness of the proposed solutions are very limited. To better solve these problems, we suggest the next minimal equipment for practically negotiated learning environment. With the following setting, the problems mentioned above can be solved substantially.

Table 2. Next minimal equipment for practically negotiated learning environment

|

Next minimal equipment |

Advantages |

Potential challenges |

Solutions |

|

|

|

|

Expanded equipment

In addition to the next minimal equipment, if budgets and circumstances allow, full-fledged equipment can be considered. We suggest the following equipment to enhance students’ satisfaction with the learning environment.

Table 3. Expanded equipment for practically negotiated learning environment

|

Expanded equipment |

Advantages |

Potential challenges |

Solutions |

|

|

|

|

Equipment used in Pilot Study

The implementation of the pilot study has taken full advantage of the current technological supplies of OIT at the College of Education. We didn’t buy any new fancy tools specifically for this project. See Table 5 for details about the hardware and software used in the pilot study. The hardware was completely provided by OIT. The software are mostly free to use at UGA (such as eLC, regular Zoom, and Google Apps.). Two Zoom pro accounts are provided to our team. The instructors have their own Pro Account, too. The desktop recording software EverLec was used because of its high uploading speed and convenience for editing at a relatively high expense.

Table 4. Equipment used in pilot study

|

Hardware |

Software |

|

– 4 displays (3 large screen displays along one wall, 1 smaller display on the opposite wall) – 1 desktop computer (both OSX and Windows available) – Set of 4 wireless microphone-speaker “pucks” – 2 laptop computers – 1 wide-angle video camera – 1 autofocus video camera with pan-tilt-zoom capability |

– Web-conferencing software (Zoom) – Desktop recording software (EverLec by Xinics) – Recording editing software (CommonsEX by XInics) – LMS (desire2learn) – Collaborate Ultra – Google docs/slides/sheets (or any other method of online document collaboration as determined by students) |

Pedagogical Practicality

In this section, we propose classroom activities to realize practically negotiated learning environments. We focus on four types, such as lecture, discussion, project, and collaboration, to illustrate how to satisfy diverse students’ needs with practical technology and pedagogy. See table 5 for a overview of the learning activities. Pedagogical strategies for each learning activity will be elaborated in the following sections.

Table 5. Summary of pedagogical strategies for practically negotiated learning environments

|

Learning activities |

Students’ needs |

Practicality |

|||||

|

Cognitive |

Affective |

Logistical |

Technology |

Modes of interaction |

|||

|

Face to face |

Synchronous |

Asynchronous |

|||||

|

Discussion |

Learning from others |

Feel safe to participate |

Anywhere & anytime |

LMS+Zoom+Screen recording |

Zoom Discussion |

Zoom discussion |

Watching recorded discussion + LMS discussion |

|

Lecture |

Knowledge from instructors |

Satisfaction with learning knowledge |

Anywhere & anytime |

LMS+Zoom+Screen recording |

Direct listening to lectures |

Online listening to lecture |

Watching recorded lecture |

|

Project |

Building own experience and knowledge |

Satisfaction with autonomous learning |

Anywhere & anytime |

Video conference tool, email |

Break out room feature of Zoom |

Break out room feature of Zoom |

Watching recorded agenda and discussion about project |

|

Collaboration |

Learning from others/ improving quality of product |

Supportive learning community |

Anywhere & anytime |

Diverse Web 2.0 tools such as Google Docs |

Screen sharing feature of Zoom |

Screen sharing feature of Zoom |

Watching recorded work |

Lecture

Instructors’ lectures and guidance are essential for any learning environment. Although information is abundant on the Web, learners still want to learn course specific knowledge and receive guidance from instructors. Learners will be satisfied with their taking the courses if they learn new skills and knowledge from instructors. In addition, some learners may want to access information from instructores anytime and anywhere. To satisfy these needs of students, technologies and practical pedagogical strategies need to be incorporated.

According to Svinicki, McKeachie, Nicol, and McKeachie (2014) lectors can provide up-to-date information, summarized material, and focused on key concepts or ideas. The role of lectures is to build a connection between a student’s past knowledge to the new subject material at hand (Svinicki et al., 2014). However, lectures do not need to be dry and boring. Barbara Davis (1993) encourages incorporating active learning into lecture. Some of her suggestions include: group activities, group discussions on certain prompts or questions, including narratives into lectures, and including student presentation as part of the lecture. Table 6 describes audio-visual technologies and exemplary activities in practically negotiated learning environments.

Table 6. Audio-visual technologies and activities for lectures in practically negotiated learning environments

|

Activity Description |

Technology |

Guidelines |

Face-to-face |

Synchronous |

Asynchronous |

|

PowerPoints or Slide Show presentation |

•Zoom (and its connected cameras and microphones) • Microsoft PowerPoint • Google Slides • Handwritten notes on a board. There would need to be a camera specifically facing the board. |

– instructor share the screen via Zoom of their presentation regarding the content of the lesson.

|

During class observation and participation

|

During class observation and participation

|

After class observation. |

|

Flipped Classrooms |

• Zoom (and its connected cameras and microphones) • recording Camera or microphone, maybe screencast-o-matic for recorded screen capture. • Zoom Breakout Room Option |

– pre-record lecture presentation provided for students ahead of time. – Plan for a class that will reinforce the pre-recorded content. |

Pre-class preparation; in class participation |

Pre-class preparation; in class participation |

Pre-class preparation; after class observation or discussion. |

|

Quizzes: pop, planned, or surveys |

• Zoom (and its connected cameras and microphones) • Online Survey service: Qualtrics, Survey Monkey, Google Survey, and more.

|

– prepare quiz material in alignment of lesson plan and lecture. – use the zoom chat feature to share a quiz/survey service link to entire class. |

In class quiz |

In class quiz |

Separate quiz for Asynchronous students to turn in post class session. |

Discussion

Discussions are very common in face-to-face and synchronous online learning environments. Students can learn from each other through discussion interactions (Han, S. Y. & Hill, J. R., 2007). However, students need to feel safe to participate in the discussion and satisfy their logistical needs to participate in the discussion anytime, anywhere. However, asynchronous discussion is difficult to make active for higher-level learning (Darabi, A., Arrastia, M. C., Nelson, D. W., Cornille, T., & Liang, X., 2011). To have discussion that actively supports higher-level learning, careful support and management is necessary.

Table 7. Discussion in practically negotiated learning environments

|

Activity Description |

Technology |

Guidelines |

|

Real-time discussion •as a class (all except for asynchronous students) |

•Zoom (audio/visual) •Zoom (chatroom)

|

As a class, Zoom audio/visual allow discussion, with the Zoom chatroom as a hybrid formal/informal space that runs parallel to the main class discussion.

|

|

Real-time discussion •mixed groups (F2F-synchronous) |

•Break out room function in Zoom •F2F students with headsets in class

|

Whereas online participants may see little to no difference, F2F students must use headsets to communicate verbally due to audio echoing in the classroom. F2F may also choose to strictly be limited to the break out room chat. Alternately, F2F students may opt to leave the classroom to interact verbally without headset. |

|

Real-time discussion •unmixed groups (F2F only, or synchronous only) |

•Break out room function in Zoom

|

The class is separated into two spaces, one for F2F and one for online. Zoom is idle, with only the instructor able to interact with the online break out rooms. |

|

Asynchronous discussion |

•LMS (D2L) |

Discussion happens in asynchronous messages. Discussion can be structured in various ways, such as having a general class space alongside spaces for each group. |

Project

Project-Based Learning (PBL) is a form of situated learning based on the constructivist theory that “students gain a deeper understanding of material when they actively construct their understandings by working with and using ideas in real world contexts.” (Krajcik & Shin, 2014). It emphasizes student-centered learning by working on authentic real-world problems. Students learn to communicate, cooperate, negotiate and think creatively and critically as they pose questions, brainstorm new ideas, research independently, and work together to finish a final product and demonstrate the project. Research has demonstrated the effectiveness and efficiency of PBL compared with traditional teacher-centered learning approach (Krajcik & Shin, 2014; Larmer, Mergendoller, & Boss, 2015). Holm (2011) indicates that PBL “is beneficial, with positive outcomes including increases in level of student engagement, heightened interest in content, more robust development of problem-solving strategies, and greater depth of learning and transfer of skills to new situations” (p. 10).

Students are often supposed to engage in project as assignments in many courses of the LDT/IDD program. Autonomous and experiential learning experience can improve students’ satisfaction from learning. Still, students need to participate in the projects meeting their logistical needs, cognitive needs and affective needs. A mixed group of all three modes of modalities, if possible, can diversify the team composition and provide different perspectives for students to enrich their learning experience like in real-world settings. The table below is created to show projects with mixed group members.

Table 8. Projects in practically negotiated learning environments

|

Activity Description |

Technology |

Guidelines |

|

Project Proposal |

LMS discussion board, Zoom meeting |

– Provide a few projects suitable for the class via LMS or class meeting presentation. – Ask the students to propose authentic projects related to their jobs or study in LMS discussion board or class meeting presentation. – Give the students some time to think and ask for more information about the projects they might be interested in. |

|

Project selection |

Zoom poll, Pollev, Google Forms, etc. |

– Provide guidelines about the number of people in each group and their roles, etc. – Create live polls for students to select their projects, using Zoom poll, Pollev, or other survey tools. – If the project ideas are on the LMS discussion threads, ask students to reply to the project threads they want to work on. – Make adjustment to the team members if necessary. |

|

Team formation |

LMS discussion board, Google drive, Google hangouts, emails, etc. |

– Provide rubrics and and guidelines about the requirements and expectations. – Instructors can create exclusive discussion thread in LMS for each team for future communication. – Each team can create a group in Google Hangouts for convenient conversation. – Each team can create a Google Drive folder to allow team members to share documents easily, if the teamwork involves a lot of files. – Students can communicate with teammates about their preferences of communication and availability, etc. |

|

Students working on projects outside class |

Zoom, Google Hangouts, Google Doc, Google Slides, etc. |

– Students work synchronously or asynchronously outside class based on their schedule, using collaborative tools, such as Google doc, google Slides, etc. – Instructor or TA can schedule separate meetings with each group to provide more specific consultant and feedback at some point of their projects or as needed. – During this process, other team management strategies are necessary as prefered by instructors. |

|

Project presentation as a group in class meetings |

Zoom |

– One of the group members is designated to share their screen via Zoom and be the controller of the slides or document as the presenters take turns to present the content. – Presentation slides are recommended to share with classmates via chat box upon presentation. – Asynchronous presenters can pre-record their part and let the other group members ( whoever is not sharing the screen) play the recording in class. It can be played by their synchronous online partners, with their headphone unplugged. It can also be played by a face-to-face student who is not sharing the screen – It is highly recommended to inform the TA and instructor beforehand of any possible plans of playing a video/audio file in the physical classroom by an onsite participant. |

|

Instructor feedback & peer feedback |

Zoom, LMS |

– Instructors and students can provide live feedback after project presentation. – Instructors and students can also provide feedback in the Discussion threads in LMS. |

Collaboration in Class

This collaboration can occur on every class bases. However, in PNLEs, it is difficult to anticipate natural collaboration between students without instructor’s guidance because three different modes of students work together. In PNLEs, computers and software tools mediate collaborative processes. Therefore, we propose that instructors incorporate strengths of computer supported collaborative learning environments (CSCLs) into PNLEs. CSCL is described as “a learning environment in which a large amount of information can be accessed easily, and in which knowledge can be shared and co-constructed through communication and joint construction of products” (O’Donnell et al., 2013, p. 266). Instructors in CSCLs focus on how to support collaborative learning processes with computers. This nature of CSCLs is well aligned with what instructors are trying to do for organizing collaborative learning activities in PNLEs because the mediating role of computers is essential in PNLEs to support collaborative learning processes between three different modes of students.

In order to support collaborative learning processes in PNLEs, we suggest that instructors provide collaboration guides for the students. The collaboration guides will specify what students are supposed to learn in the collaboration, how students form groups, what roles students play in collaboration, and what types of final product students generate as the result of collaboration (Kollar et al., 2006). Table 3 displays collaboration activities and collaboration guides that can support three modes of students

Table 3 Collaboration activities in PNLEs

|

Activity Description |

Technology |

Collaboration guides |

Face-to-face |

Synchronous |

Asynchronous |

|

Collective knowledge building through wiki platform (see Screenshot 1) |

Wikispace, Mediawiki, Wiki (enhanced) in Moodle, Tiki Wiki |

-Forming three different modes of students in a group -Specifying learning goals -Providing worked examples -Offering procedural guides -Specifying roles to play in creating wiki |

During class editing |

During class editing |

After class editing |

|

Collective knowledge building through websites (see Screenshot 2) |

New Google Sites, WordPress, Google Blogger, Wix |

-Forming three different modes of students in a group -Specifying learning goals -Providing worked examples -Offering procedural guides -Specifying roles to play in creating web pages |

During class editing |

During class editing |

After class editing |

|

Social Mapping (see Screenshot 3) |

Google MyMaps |

-Forming three different modes of students in a group -Specifying learning goals -Providing worked examples -Offering procedural guides -Specifying roles to play in creating maps |

During class mapping |

During class mapping |

After class mapping |

|

Collaborative rating (see Screenshot 4) |

Pyramid App |

Forming three different modes of students in a group -Specifying learning goals -Providing worked examples -Offering procedural guides -Specifying roles to play in collaborative rating |

During class rating |

During class rating |

After class rating |

Screenshot 1

Screenshot 2

Screenshot 3

Screenshot 4

Recommendations for implementation

Prior to course beginning

- Establish contact with OIT to do a tour of possible classrooms and to be informed of each classroom’s technological capabilities and limitations.

- Once a classroom (or classrooms) has been decided on, contact the College to reserve the classroom times:

- 1 to 1.5 hours before class begins (reserve as an “event”)

- 3 hours during class (reserved as the class time proper)

- 1 hour after class ends (reserve as an “event” if there are potential events or classes afterwards)

- Establish a designated person at the OIT as an official contact. This contact person will first and foremost ensure the availability of the required equipment for the above times. The contact should also be on hand during setup and testing in case of equipment failure, provide alternate equipment if necessary, and if applicable, use their administrator access to update/install software when necessary.

Setup for a typical class

- Setup time: TA should arrive to prepare at least 1 hour or 1.5 hours before the class begins to begin setup and testing of equipment.

- Teardown time: TA should expect to spend between 0.5 and 1 hour to ensure transfer of the recording file and teardown of equipment.

- Instructor should allow 10-15 minutes to get himself/herself prepared.

- Check-out/gather necessary equipment from OIT, including power strips and extension cords

- Furniture arrangements: arrange the tables and chairs in a way to get the onsite participants as close to each other as possible; this may change to suit certain classroom activities.

- Setup equipment

- Test equipment

- Tests for camera angles should be done via Zoom

- Recording test must involve a verbal interaction between online and onsite participant(s).

- Have the Zoom accounts connected to the cameras and microphone join the host Zoom room (if they are not already the host)

- Begin the screen recording shortly before class begins

Note on the screen recording

- If the class recording will not be edited on the computer it was recorded on, the recorded file will likely need to be copied to USB in order to transfer to the computer that will do the video editing.

- If the session was recorded via Zoom, the Zoom recording must be converted to mp4 in order to edit. It is a lengthy process to convert Zoom recording to mp4. If the computer you are using is a public desktop one, you will need to save the Zoom recording file onto a USB drive, then save it to a personal computer and convert from Zoom to mp4.

- EverLec screen recording transfers to their cloud platform, which takes about 15 minutes for a 2.5 hour recording to upload. Editing can then be done through their cloud platform.

Challenges & Recommended Solutions

|

Challenge |

Solution |

|

Audio feedback in classroom |

Ensure that any computer logged into the Zoom classroom: 1) In Zoom: Has the mic icon set to mute (or ensure that person has not joined audio) 2) On the computer: Has the computer speaker volume set to 0. |

|

Instructor or face-to-face students want to play video with sound. |

1) Ensure that the Zoom host has enabled only 1 computer may share a screen at a time. 2) Determine which computer the video will be played from. 3) Confirm that computer is connected to the Zoom classroom. 4) In Zoom: “Leave computer audio” via the Microphone arrow tab. 5) On computer: unmute and increase speaker volume 6) In Zoom: Click on Share Screen menu 7) In Share Screen option page: check the box titled “Share computer sound.” And share desktop. 8) Play video. |

|

Online synchronous students want to play video with sound. |

1) Make sure screen share has checked the box titled “Share computer sound.” 2) If using headset, disconnect the headset. 3) Play video once screen is shared. |

|

Onsite group presentation involves pre-recorded audio embedded in a powerpoint |

Group should use 2 computers for the presentation. One to share the screen (and PPT) with the class, while the other computer plays the relevant audio file. The wireless mic should be moved close to the computer playing the audio. |

|

The cable connecting the mic-speaker system to the main computer designated for recording is disconnected accidentally. |

1) Instructor or students should announce in chat that the audio has been cut off. 2) Recording should be paused. 3) Cable should be reconnected. 4) Recording should resume after Zoom has re-oriented to the desired speakers. |

References

Bates, A.W. (2015) Teaching in a digital age: Guidelines for designing teaching and learning. Vancouver, BC: Tony Bates Associates Ltd.

Bower, M., Dalgarno, B., Kennedy, G. E., Lee, M. J. W., & Kenney, J. (2015). Design and implementation factors in blended synchronous environments: Outcomes from a cross-case analysis. Computers & Education, 86, 1-17.

Bower M., Kenney, J., Dalgarno, B., Lee, M. J. W., & Kennedy, G. E. (2014). Patterns and principles for blended synchronous learning: Engaging remote and face-to-face learners in rich-media real-time collaborative activities. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 30(3), 261-272.

Butz, N. T., Stupnisky, R. H., Peterson, E. S., & Majerus, M. M. (2014). Self-determined motivation in synchronous hybrid graduate business programs: Contrasting online and on-campus students. Online Learning and Teaching, 10, 211-227.

Cain, W., Bell, J., & Cheng, C. (2016, July). Implementing robotic telepresence in a synchronous hybrid course. In Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 2016 IEEE 16th International Conference on (pp. 171-175). IEEE.

Darabi, A., Arrastia, M. C., Nelson, D. W., Cornille, T., & Liang, X. (2011). Cognitive presence in asynchronous online learning: a comparison of four discussion strategies. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 27(3), 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2010.00392.x

Davis, B. G. (2009). Tools for teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Garrison, D.R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. Internet and Higher Education, 2, 87–105.

Han, S. Y. & Hill, J. R. (2007). Collaborate to Learn, Learn to Collaborate: Examining the Roles of Context, Community, and Cognition in Asynchronous Discussion. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 36(1), 89–123. https://doi.org/10.2190/A138-6K63-7432-HL10

Hannafin, M. J., Hall, C., Land, S., & Hill, J. (1994). Learning in Open-ended Environments: Assumptions, Methods, and Implications. Educational Technology, 34 (8), 48-55.

Henriksen, D., Mishra, P., Greenhow, C., Gein, W., & Roseth, C. (2014). A tale of two courses: Innovation in the hybrid/online doctoral program at Michigan State University. TechTrends, 58, 45-53.

Hill, Domizi, Kim, & Kim. (2013). Teaching and learning in negotiated and informal online learning environments. In M. G. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of distance education (3rd edition), pp. 372-389. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hill, J. R., Domizi, D. P., Kim, M., & Kim, H. (2013). Learning perspectives on negotiated and informal technology-enhanced distance education: Status, applications and futures. In M. Moore (Ed.), Handbook of Distance Education (3rd ed.) (pp. 372-389). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Holm, M. (2011). Project-Based instruction: A review of the literature on effectiveness in prekindergarten through 12th grade classrooms. InSight: Rivier Academic Journal, 7(2), 1.

Irvine, V., Code J., & Richards L. (2013). Realigning higher education for the 21st century learner through multi- access learning. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 9(2), 172-185.

Kollar. I, Fischer. F, Hesse, F. (2006). Collaboration scripts – A conceptual analysis. Educational Psychology Review, Springer Verlag, 18(2), 159-185.

Krajcik, J. S. & Shin, N. (2014). Project-Based Learning. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (2nd ed., pp. 275-297). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Land, S.M., Hanafin, M. J., & Oliver, K. M. (2012). Student-centered learning environments: Foundations, assumptions, and design In D. Jonassen & S. M. Land (Eds.), Theoretical foundations of learning environments (2nd edition), pp. 3-25. New York, NY: Routledge.

Larmer, J., Mergendoller, J., & Boss, S. (2015). Setting the standard for Project-Based Learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

O’Donnell, A. M., Hmelo-Silver, C. E., & Erkens, G. (2013). Collaborative learning, reasoning, and technology. New York, NY: Routledge.

Richardson, J. C., Maeda, Y., Lv, J., & Caskurlu, S. (2017). Social presence in relation to students’ satisfaction and learning in the online environment: A meta-analysis. Computers in Human Behavior, 17, 402-417.

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Svinicki, M. D., McKeachie, W. J., Nicol, D., & McKeachie, W. J. (2014). McKeachie’s teaching tips: Strategies, research, and theory for college and university teachers. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.